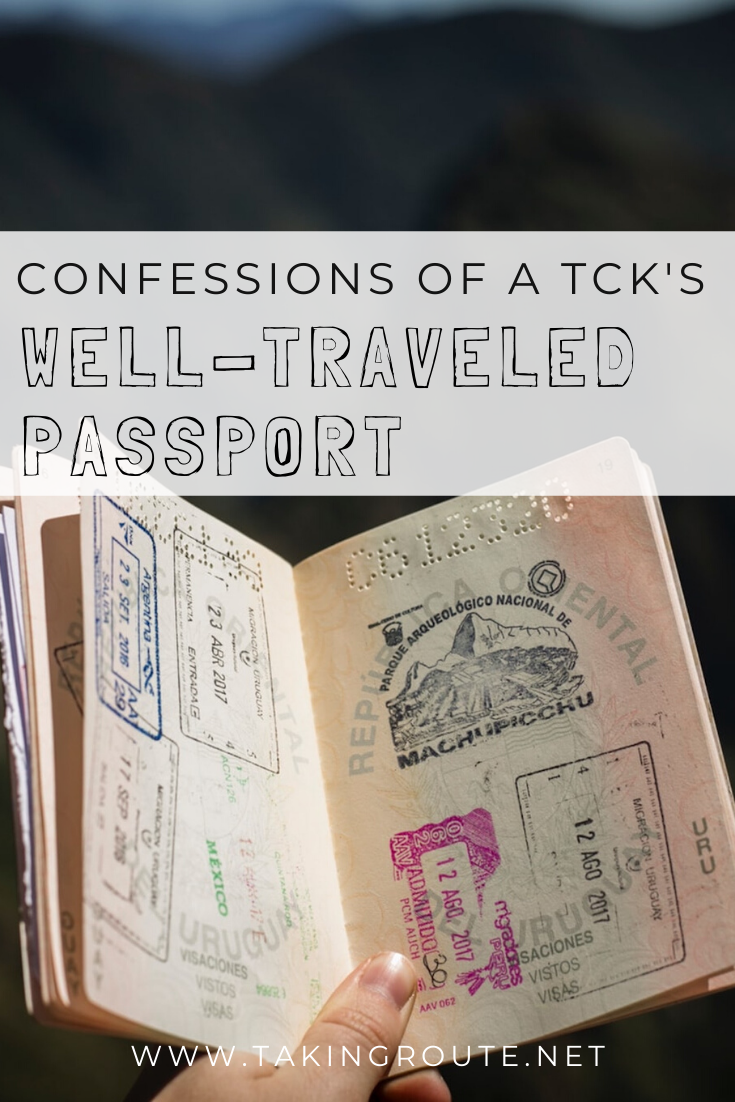

Confessions of a TCK's Well-Traveled Passport

“That passport was a record-keeper for my personal goal to visit as many countries as I was old. It was stamped with experience after experience, memory after memory, the currency of a TCK life.”

When I was in college, I lost my passport.

At the time, I studying in the States and my parents were living in Kenya and I was scheduled to fly there for Christmas a few short weeks later. Honestly, looking back now, my parents were way too nice about this, and we got an expedited new one that arrived in time for me to still be able to go. I probably was not as stressed as I should have been about getting the replacement (nor felt as guilty as I should have about losing it in the first place), but I did feel the loss of that passport – the actual object itself – deeply.

As a TCK, that passport contained stamps that were tied to important places and memories. It had my visa for Ethiopia, the country I grew up in but was not returning to. It had the stamp for Egypt, where I went on my senior class trip right after graduation with my tight-knit class of ten, one final hurrah for a life I was devastated to see come to an end. It had the stamp for when I traveled with my best friend’s family to England on the way back to the States; the time I got to miss two weeks of school to tag along to India with my parents for work; the family vacations to Kenya; the random trip to China with college friends where my friend Lauren cried on the Great Wall because it was so cold; and, of course, the exciting and awkward re-entries to the USA every other summer. That passport was a record-keeper for my personal goal to visit as many countries as I was old. It was stamped with experience after experience, memory after memory, the currency of a TCK life.

Maybe it seems too on the nose for the passport to be a symbol of TCK’s life, but as I consider the weight I’ve put on my own – the way I felt those feelings of loss all over again even as an adult when I had to get a new passport with my married name – I can see some of the truths and realities about my TCK identity revealed. In case you have your own TCKs that you are trying to understand, or you see these things reflected in your own story as a third culture adult (sure, you can be that!), here are some things I’ve realized my passport shows about my TCK identity:

My passport is a physical manifestation of many of the things I take pride in about my TCK identity: travel, experiences, and a global worldview. These are the flashy and fun parts of my TCK life, the parts I can’t talk too much about in certain situations because it comes across as bragging (and sometimes maybe it is). There are plenty of not-so-fun parts of this life – the many goodbyes and being far from family for starters – but there are glorious adventures, too. Getting to explore different parts of the globe and travel becoming second nature are the hallmarks of growing up overseas, and rest assured that I know no adult TCKs who regret this part of their upbringing. Passports are the record keeper of these things.

My passport is a shorthand for communication with other TCKs. A well-worn passport is a connection point – an “oh, you do this too” moment of shared commonality. It might quickly turn to competition (I’ve rarely been amongst other TCKs – my husband included – where we haven’t pulled out our passports to compare stamps) but in a way that, under its surface, is fostering connection. The authors of Third Culture Kids: The Experience of Growing Up Among Worlds wrote that, “a sense of belonging is in relationship to others of similar background.” In this shared language of passports – full-page visas, unfortunate photos, and official stamps – we find that.

And lastly, I think my passport serves as a guarantee that this life isn’t over, and I can go back. Or, even if I can’t go back, I can go somewhere, which is a fair substitute. For many TCKs, it can be difficult to return to their passport country, especially permanently. Saying goodbye to not just the place that is home, but also that way of life and the people who understand it is something that has to be grieved. In this context, a passport not only carries the memories of the past but also a promise that in the future they might be able to return.

Are these things part of your own lived experience, or things you are starting to see in your kids? If it’s not a passport, is there another object that carries the emotional weight of your cross-cultural experiences?